Combinatorial crosswords

Today’s post is inspired by the July 13, 2024 Vox daily crossword puzzle. The post will spoil the clues, so if you want to cross the words first, you should do that then read this post.

The spoilers

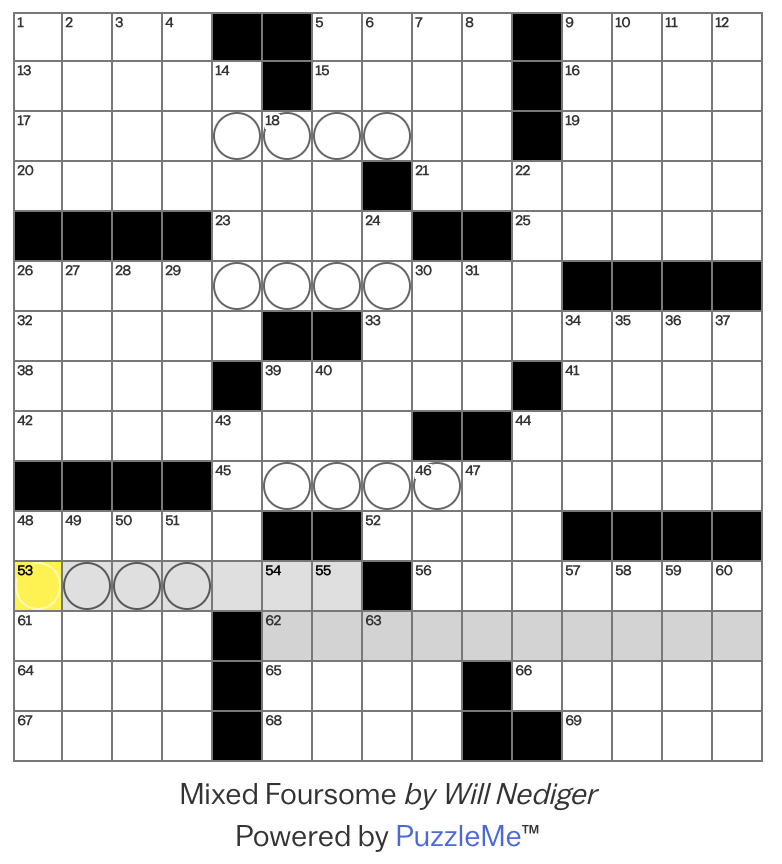

Here’s the blank puzzle:

Do you see the four times that there are four circled boxes in a row? They are crucial to our theme.

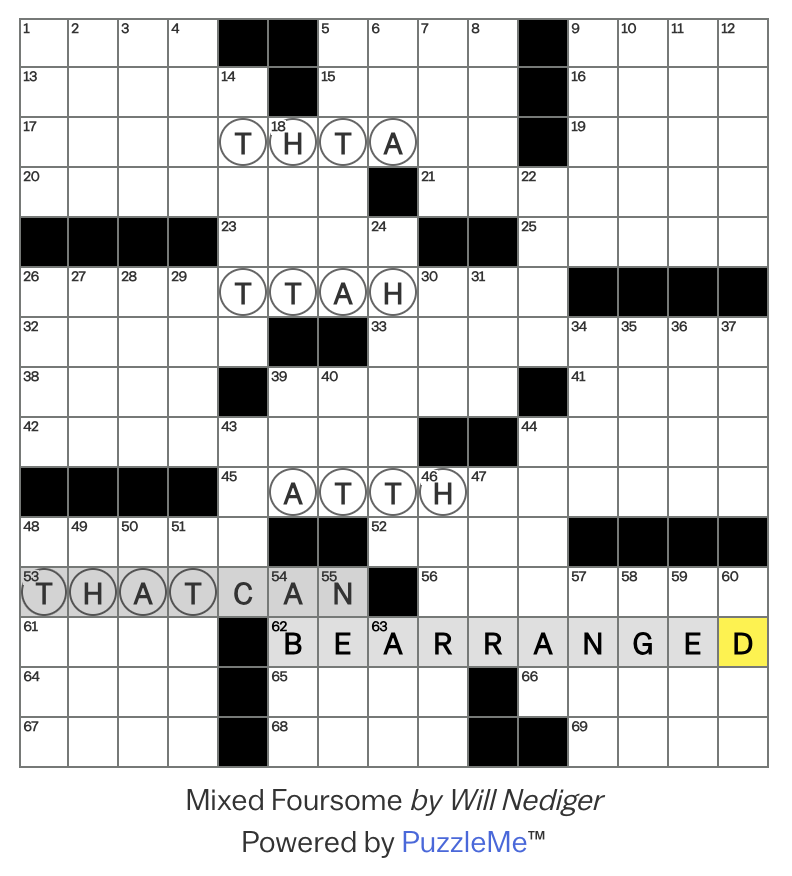

The clue for 53-Across hinted at the theme:

“With 62-Across, “We’ll make it happen” … or a fact demonstrated by this puzzle’s theme entry?”

The answer? “THAT CAN” and 62-Across was “BE ARRANGED”. The joke is that the letters “t”, “h”, “a”, and “t” can be rearranged to fill in the other squares with circles. I like it! Without spoiling the whole puzzle, here are the correct solutions for those other boxes:

A first question

The puzzle maker included four of the possible ways to rearrange “that”. Did they include all of them? In other words, how many possible ways are there to rearrange the letters in “that”?

The naive first answer someone might say is that there are “24” ways to rearrange the letters in “that”; there are 4 choices for the first letter, then 3 for the second, then two for the third, and then we have to use the last letter remaining. In other words there are \(4! = 4\cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 = 24\) ways. 24 is the right answer for asking how to rearrange “That”, but not “that”. Why? Because two lowercase t’s are indistinguishable. The words “thaT” and “That” are different, but when the letters are all lowercase, “that” and “that” are the same.

If I take any rearrangement of “that”, and want to capitalize exactly one of the t’s, there are two ways to do it. For example, take the rearrangement in the top part of the puzzle: “thta”. I could get “Thta” or “thTa” out of it. So there are two rearrangements of “That” for every rearrangement of “that.” If we use the variable \(T\) to describe the number of rearrangements of “That”, and the variable \(t\) to describe the number of rearrangements of “that”, then the statement

So there are two rearrangements of “That” for every rearrangement of “that.”

is equivalent to the equation \(2\cdot t = T\). So we can solve \(2 \cdot t = 24\) for \(t\) to see that there are \(12\) ways to rearrange “that”. It does seem like it would be hard to fit all 12 ways into a single 15-by-15 crossword grid… but these puzzle makers are pretty creative!

A harder question

Running through the heart of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus is the majestic Mississippi river. “Mississippi” has a lot of letters, and a lot of repeated letters! How many ways are there to rearrange the word “Mississippi”? Should I challenge a crossword puzzle maker to include some rearrangements of Mississippi in puzzle?

We could answer the question using the same technique we used to answer the question about rearrangements of “that”. If we wanted to do that, we have a lot more bookkeeping to do. For example, there are four i’s in Mississippi. So that means that every configuration of i’s comes from not just two but \(4!\) different rearrangements of the letters. But it gets even harder because now there are multiple i’s and multiple s’s and multiple p’s. One way to make all of this bookkeeping easier is to think about how to incorporate formal mathematical notions of symmetry into the picture. Let’s introduce these formal mathematical notions before we return to rearranging the Mississippi.

Mathematical symmetry

The fundamental structure that mathematicians use to capture symmetry is called a “group.” Groups have two pieces of information: the elements, and the operation. The operation takes two elements, and tells us how to combine them to get a new element. (There is actually a little bit more to say if I wanted to be completely precise, but you can read about that on Wikipedia).

To make this a little closer to home, I want to point out that there is one group that you work with every single day. That group is called \(\mathbb{Z}/24\). The elements are the numbers \(0,1,2,3,\) and so on, up to and including \(23\). The operation is simple to describe: add the two numbers together. So for example \(3 + 7 = 10\) in the group. We took two numbers \(3\) and \(7\) and combine them to create our new number \(10\). All of these numbers are elements of the group. Another example: let’s combine \(2\) and \(22\). We see that \(22 + 2 = 24\). Oh no! \(24\) is not an element of the group! What do we do??

The answer is the same as if you get asked to go to a two-hour show that starts at 10pm (22h in 24-hour time). You will get done at midnight, or 0h in 24-hour time.

What about \(21 + 8\)? That has the same answer as the question, if I go to bed at 9pm (21h), what time will I wake up, after 8 hours of sleep? In either case, the answer is \(5\).

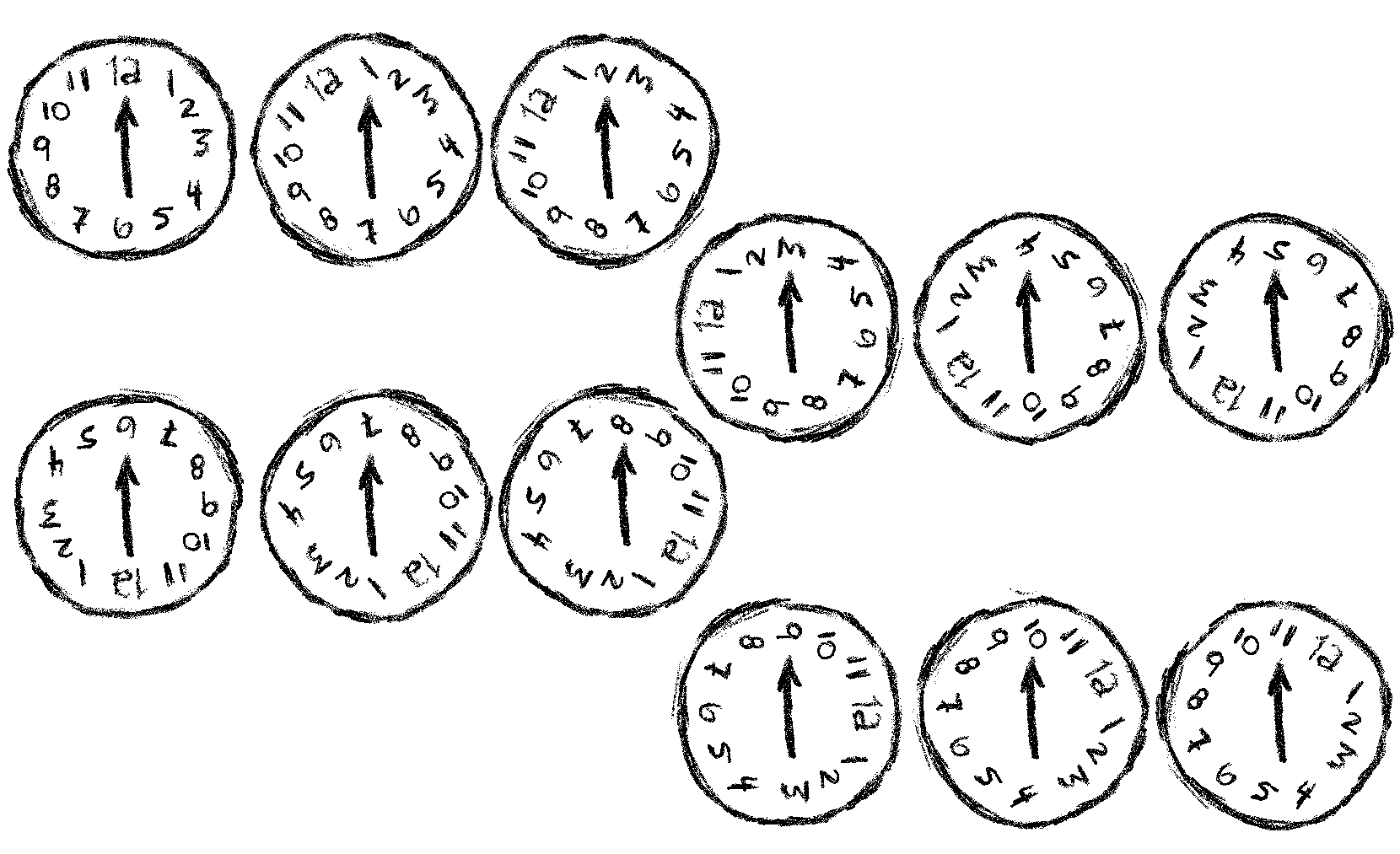

Now that you know what the group \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) is, you could very reasonably ask the question, “how in the world does this encode symmetry?” Well in this case, it encodes the rotational symmetry of the hour ticks on a 24-hour clock like this one:

(Image from Wikipedia, courtesy of Christine Matthews under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license)

Usually we think about the hand on a clock moving, but Albert Einstein, who discovered the theory of relativity, would have told us that we can think of the clock itself moving, with the hand always pointing straight up like it was midnight, then every hour, the clock would rotate counter clockwise one tick. So the group \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) encodes the symmetry of the hours in the day.

Since \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) encodes the symmetry of hours in the day, and 12-hour clocks encode the information of hours in the day, \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) should somehow be related to the symmetry of a 12-hour clock. But there is something funny that happens here! On the twelve hour clock, the symmetry of the hours doubles up! We can follow the same rule that the group \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) encodes the symmetries of a 12-hour clock by rotating it every hour.

But now here, once we have gone up to twelve, we end up back at the same place! This gives us a very special collection of elements of \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) called “the stabilizer of the action on the 12-hour clock.” Those elements are \(0, 12\). Notice that they have the special property that if I add them together in any way, my set doesn’t get any bigger! This says that \(0, 12\) is a “subgroup” of In more elementary terms, what this is saying is that, even though there are 24 hours in the day, if you add 12, you stay at the “same time”: 12 hours after 6 o’clock is still 6 o’clock.

Even though \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) has 24 elements, it still encodes the symmetry of a 12 hour clock. This is not a problem at all. In fact, it is very helpful to us. The possible configurations of the 12 hour clock could be mathematically called the “orbit” of the \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) action on the clock. Notice the fact that the size of the “stabilizer” is \(2\), the size of the “orbit” is \(12\), and the size of the group is \(24 = 2 \cdot 12\).

This is not a coincidence! The so-called “orbit stabilizer theorem” says that the size of the orbit times the size of the stabilizer will always be the size of the group.

Bringing it back to “that” and “Mississippi”

When we talk about rearrangements of a bunch of letters, there is a specific group we want to bring into the picture. That group is called the “symmetric group.” While all groups encode symmetry, the “symmetric group” is in some sense the “biggest, most symmetric of all the symmetries.” There is a way to say that precisely, but it isn’t important to us right now, so I don’t want to worry about it. If you are really worried about it, you can think of the symmetric group as encoding the symmetries of all ways to shuffle a deck of cards. The operation is to rearrange rearrangements. Meta!

In the same way that I defined \(\mathbb{Z}/24\) as the symmetries of hours in the day, the symmetric group tells us all the ways to rearrange the letters in a word with distinct letters. It depends on the number of letters in the word, so we call it \(S_n\), where \(n\) is the number of letters in the word. We saw in the example of “That” with a capital “T”, that there were 24 possible rearrangements of 4 distinct letters. So that tells us that \(S_4\) has 24 elements. (It is not the same as \(\mathbb{Z}/24\), the 24 just a numerical coincidence.)

On the other hand, when we worked with the lowercase “that”, there were two letters that were the same. In this case, the “orbit” is all of the possible rearrangements, and the “stabilizer” is the collection of elements which preserve “that”. The there are two things that stabilize “that”: the “do-nothing” symmetry, and the symmetry that tells us to swap the first and fourth letters (“thaT” symmetry).

So the orbit-stabilizer theorem tells us that there are \(24/2\ = 12\) possible ways to rearrange the word “that.”

Now we have the technology to answer the question “how many ways are there to write ‘Mississippi’?” There are 11 letters in total, so we want to start with the group \(S_{11}\). There are \(39916800\) elements of \(S_{11}\). Thankfully, there aren’t quite that many ways to rearrange “Mississippi.”

There are 4 “i’s”, 4 “s’s” and 2 “p’s”. That means that the stabilizer consists of all ways to rearrange the “i’s” (which on its own is \(S_4\)), all ways to rearrange the “s’s” (alone, another \(S_4\)), and the ways to swap or not swap the “p’s” (on its own \(S_2\)).

Since they all occur at once, we combine them into a bigger stabilizer subgroup that we call \(S_4 \times S_4 \times S_2\). The \(\times\) is an appropriate notation, because this group \(S_4 \times S_4\times S_2\) has \(24 \cdot 24 \cdot 2 = 1152\) elements. (At this point it isn’t important exactly what the exact structure of \(S_4 \times S_4\times S_2\) is, just that it has 1152 elements.) So the orbit stabilizer theorem tells us that the number of ways to rearrange “Mississippi” is \[ \frac{39916800}{1152} = 34650. \]

Considering that there are at most 225 squares in a 15-by-15 crossword, I think it would be a bit rude to challenge any crossword maker to include all rearrangements of Mississippi.

Anyways, thanks for reading! That’s that!